Environment Focus

An environmental lens on policies for better lives

Greening the recovery from COVID-19: how sustainable will it be?

By Andrew Prag, OECD Environment Directorate

When COVID-19 began to spread around the world, it brought with it many uncertainties. But one thing was quickly clear: the depth of the economic and social crisis was going to require massive government intervention to rescue jobs and livelihoods, and to reinvigorate economic growth.

A wide chorus of voices, including the OECD, quickly began to call on governments to think beyond a pure economic recovery as they prepared these interventions. Study after study pointed to the opportunities for investing in greener technologies and infrastructure as a way to not only create jobs and reignite growth, but also to finally shift us onto a more sustainable path: an opportunity to combat climate change, biodiversity loss and other environmental crises head-on. And as the pandemic had brutally reminded us of our fragile relationship with, and dependence on nature, the case had never seemed clearer.

Encouragingly, many governments appeared to heed the call, with leaders lining up to commit to a “green recovery” and to “building back better” through the national and sub-national stimulus packages under preparation.

By early 2021, at least USD 14 trillion had been announced across OECD and key partner countries, much of it emergency health funding and rescue spending aimed at keeping businesses and livelihoods afloat through the worst of the crisis. But as more countries have moved on from rescue spending towards announcing their stimulus and recovery packages, the question is: how green are those packages really?

The OECD Green Recovery Database tracks environmentally focused measures in member countries and key partners – most of the G20 countries – and assesses whether they are likely to have positive, negative or mixed impacts across several environmental dimensions, ranging from climate change and biodiversity loss to pollution and waste management.

USD 336 billion – but is it enough?

The database shows that around USD 336 billion has so far been allocated to environmentally positive measures. At face value, this is an enormous sum and testament to efforts by several governments to ensure that recovery measures are oriented towards environmental goals as well as economic ones (Figure 1). And that total does not include potential new green spending from the EU-wide recovery funds that have not yet been allocated to member states (shown as a hatched bar here). So the total is set to grow as new measures come into being.

However, nearly the same amount has been spent on measures tagged as being negative, or at best mixed, for the environment. Negative measures include, for example, those directly supporting fossil-fuel related developments. Mixed measures are those that may be positive for one environmental dimension (such as climate) but damaging for others (such as biodiversity). In other words, support continues to flow to potentially harmful activities in almost equal volume to that flowing to green measures, putting at risk hopes of progress towards needed transformational change.

Figure 1: Total funding allocated to recovery measures, by environmental impact category

Note: NGEU-30 = Next Generation EU, the EU recovery fund. The funding indicated here represents 30% of the total NGEU allocation, i.e the proportion that will be earmarked for climate-related investments (including the Recovery and Resilience Facility and ReactEU). The remaining 70% of the total has been marked as “indeterminate” and so does not feature in the analysis. Note that the NGEU funding is available to all EU27 countries, some of which are neither OECD members nor accession/key partners and so are otherwise not covered in the database.

Source: OECD Green Recovery Database

Still a small part of the pie

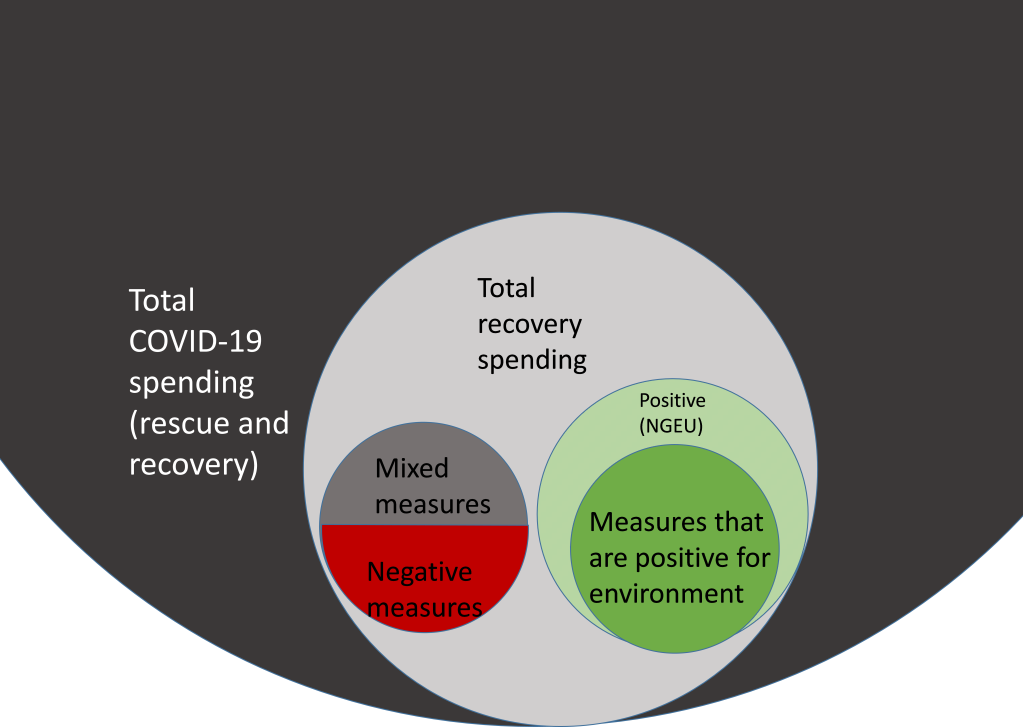

The recovery measures tagged as environmentally positive make up only around 17% of total estimated COVID-19 recovery spending announced to date, drawing on a total estimated from Global Recovery Observatory data (Figure 2). This is a small slice of the pie, given the strong support for green recovery voiced by many governments around the world. And the negative and mixed measures make up another 17% of the total.

So what about the remaining two thirds, which has not (so far) been categorised as directly impacting on the environment, whether positively or negatively? We should not assume that such measures are environmentally benign. On the contrary, the small percentage of measures tagged as “green” implies that total stimulus packages overall still lean heavily towards investments in business as usual type activities, rather than the transformational investments required. And the weight of green measures looks even smaller when compared to total COVID-19 related spending: they account for barely 2% of total spending on COVID-19, when the vast sums spent on emergency rescue funding are counted as well as the more forward-looking recovery packages.

Figure 2: Environmental measures are dwarfed by overall COVID-19 spending

Source: OECD Green Recovery Database (for Positive, Mixed and Negative totals). Global Recovery Observatory (for total COVID-19 recovery and rescue & recovery spending)

What can we learn from looking into the numbers?

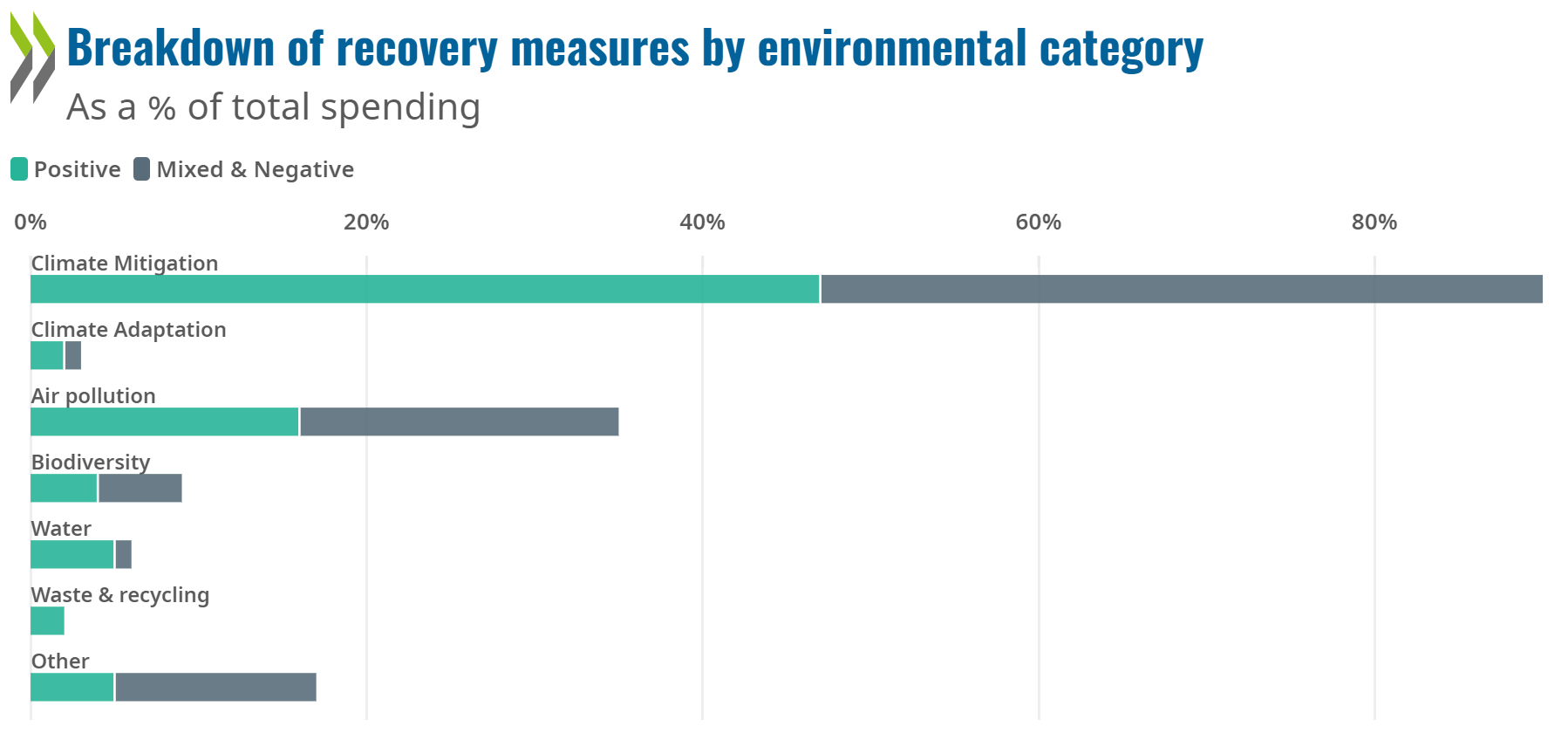

Greenhouse gas emissions: although the database tracks impacts across several environmental dimensions, by far the most commonly tagged dimension relates to mitigating climate change, i.e. influencing greenhouse gas emissions. Nearly 90% of funding allocated to measures impacting the environment is estimated to have clear implications for greenhouse gas emissions, roughly evenly split between measures that reduce emissions and those likely to increase emissions and counteract mitigation efforts (Figure 3).

Air pollution: The next most common dimension impacted is air pollution (with around a third of total funding, again evenly split), partly because of the synergy with climate measures, meaning that many measures are categorised as being positive (or negative) for both climate and air pollution simultaneously.

Biodiversity, water, waste and recycling: other environmental dimensions feature much less strongly. Measures affecting biodiversity account for less than 10% of the funding allocated, despite biodiversity frequently cited as priority for governments. Within that 10%, less than half is for measures judged to be actively tackling biodiversity loss. Water accounts for only 8%. Other important dimensions such as waste and recycling, and climate change adaptation, have so far also received a very small proportion of total funding.

Figure 3. Proportion of total funding allocated to measures impacting different environmental dimensions

Source: OECD Green Recovery Database

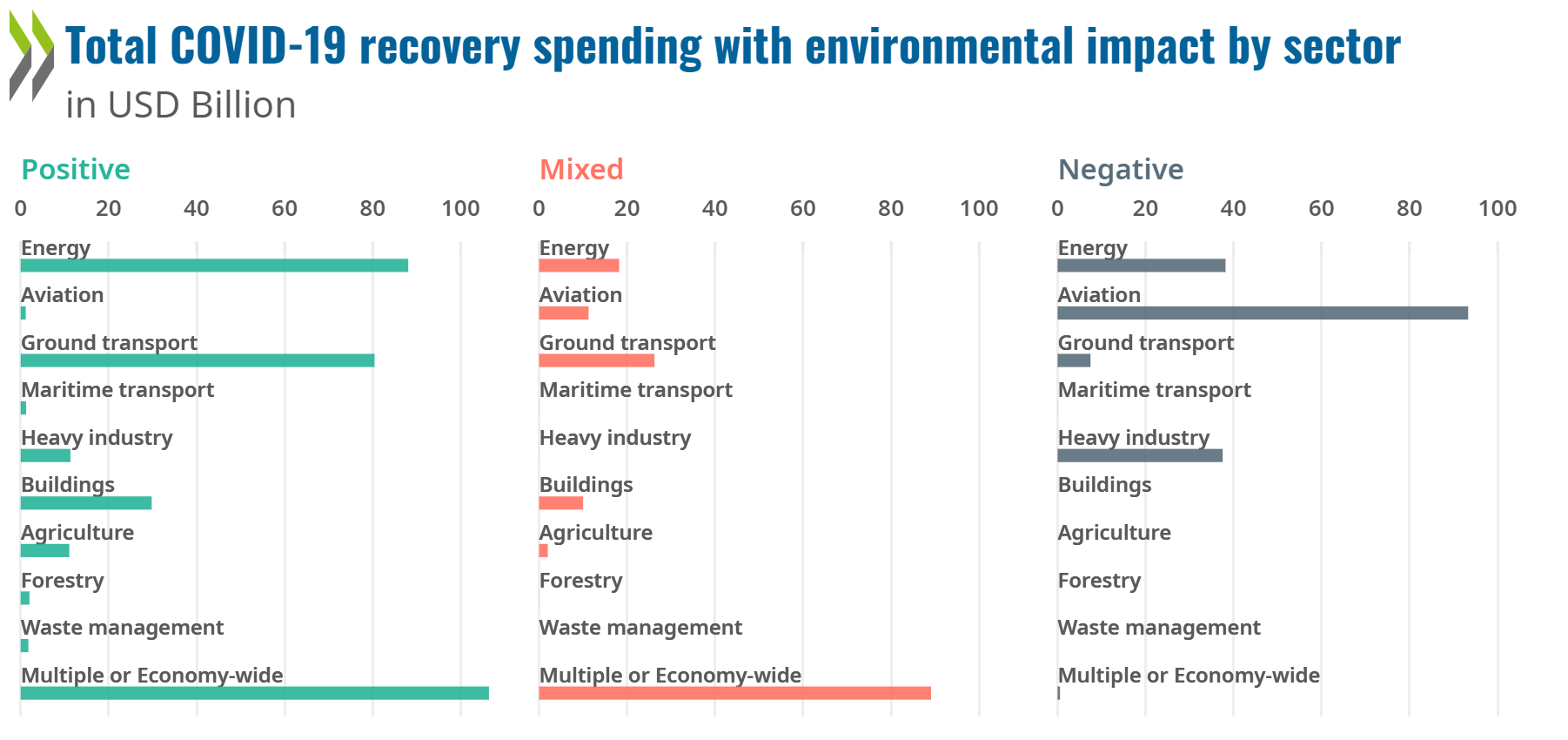

The data also reveal which sectors have been targeted by recovery measures (Figure 4).

Energy and surface transport: Energy and surface transport are by far the largest recipients of environmentally positive measures. These sectors are often in the spotlight because they account for a high proportion of GHG emissions in many countries. In addition, energy and ground transport sectors are often good candidates to have “shovel-ready” projects in the pipeline – for example renewable electricity projects and electric vehicle infrastructure – that can be rolled out or accelerated as a quick response to the economic crisis. Encouragingly, those sectors show a greater proportion of positive measures than mixed or negative ones.

Aviation and industry: On the other hand, measures for key sectors like aviation and industry show an overwhelming balance towards mixed and negative categories. Additionally, the lack of funding towards environmentally important sectors such as agriculture and forestry also points towards missed opportunities for further greening the recovery – especially given existing substantial and often environmentally questionable subsidies for agriculture).

Green skills and innovation: The data can be sliced and diced in other ways, too. For example, measures targeted at cultivating green skills and innovation appear to be surprisingly under-represented in the recovery measures announced to date.

Figure 4: Funding allocations across sectors, by environmental category

Source: OECD Green Recovery Database

How can we do better on green recovery?

Overall, the database yields a mixed picture. There are very encouraging efforts in some areas and by some countries, but still a striking level of support for environmentally damaging activities elsewhere. But, crucially, it is not too late.

Many countries are still in the process of moving from the rescue phase to the recovery phase. In the United States, for example, President Biden recently proposed a significant recovery, infrastructure and jobs package, the American Jobs Plan, which could substantially shift the dial in the green direction. At the same time, all countries are currently preparing for the COP26 climate conference, with increasing momentum towards boosting their climate commitments for the near- and longer-term.

Such commitments cannot be seen in isolation of these once-in-a-generation stimulus packages. There is still time to develop and implement a green and inclusive recovery.

Further reading:

OECD Green Recovery Database and related data viz

OECD Policy Response Brief: The OECD Green Recovery Database: Examining the environmental implications of COVID-19 recovery policies

Making the green recovery work for jobs, income and growth

Building back better: A sustainable, resilient recovery after COVID-19

Greening the recovery from COVID-19 is the question that we want to focus on. Thank you 😊

LikeLike